Above: Ken Goldman. Jacob’s Ladder Triptych, 2015. Chromaluxe print after performance. Photos by Gideon Cohen

Like any proper resident of the Netherlands, sometime in late July I pack my bags, load the car, and drive with my family to the South of France for a few weeks of Mediterranean sun and relaxation. We usually make stops in between, exploring a random French village I found online and staying at a charming country inn. Amazingly, this annual summer pilgrimage to the beach parallels the summer plans of many Jews in the Middle East in the first half of the twentieth century. The only difference is that instead of heading to the South of France to enjoy the Mediterranean, Middle Eastern Jews would travel to the seaside and mountain resorts of Lebanon, Mandate Palestine, and Egypt, often casually crossing borders in a way almost unthinkable to us in the twenty-first century. While today it would be, to say the least, unlikely for a resident of Baghdad to hop in a car and drive to Tel Aviv for a beach holiday, this was quite normal throughout the 1920s and 1930s, especially for members of Baghdad’s vibrant Jewish community. In fact, according to Google Maps, the drive from Baghdad to Tel Aviv, at 1032 km, is about 300 km shorter than my traditional summer trek from the Hague to Nice.

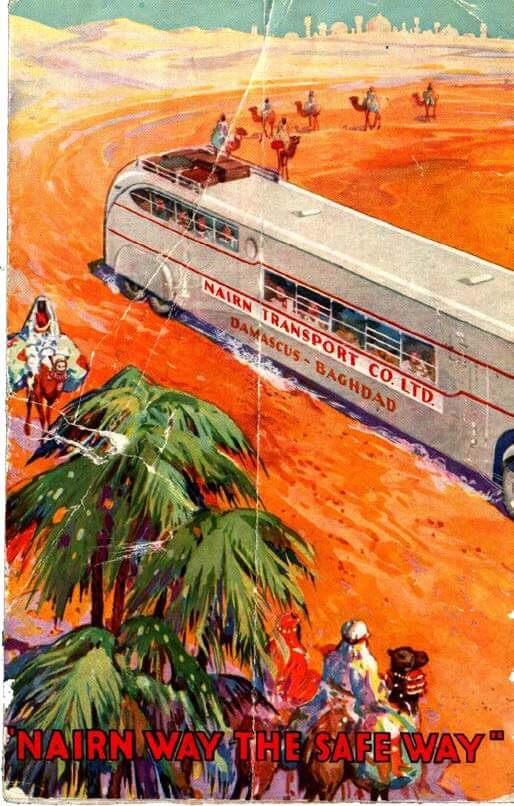

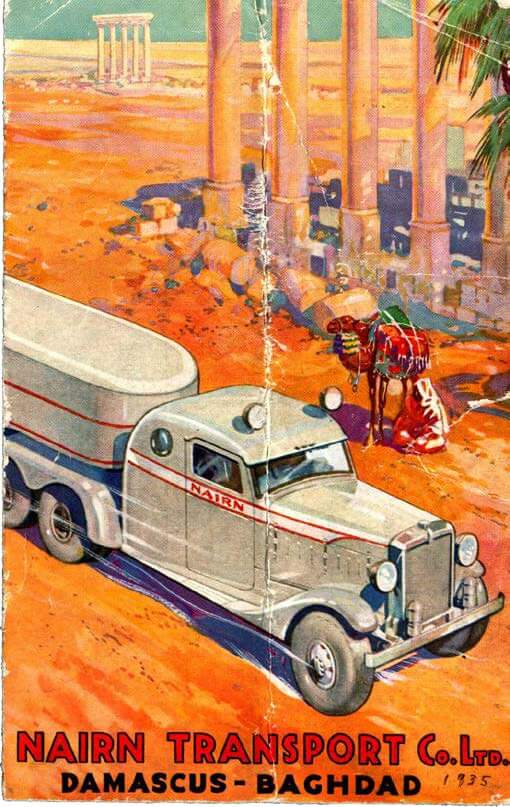

Nairn Transport Co. Ltd. brochure, c. 1935. Northwestern University Transportation Library

In the first half of the twentieth century, the urban Jewish communities of the Middle East included a flourishing middle class with both the time and the means for regional tourism. Encouraged by safe and affordable public and private transport options, in addition to a thriving tourism industry, the Mediterranean coast was, in more ways than one, a hot spot of summer leisure for urban Jewish communities looking to unwind. For Jews in Cairo, Alexandria and the Egyptian beach resorts around the Nile Delta were the most popular summer destinations. Families would either drive or take the fast train to reach seaside residences that ranged from rental apartments and hotels to a mattress in a cousin’s home. Inevitably these lodgings were never far from a kosher butcher or pop-up synagogue catering to Jewishholi daymakers. Families would frequently pair up to rent villas on the beach, nearly a century before Airbnb came into existence. Memoirs from the interwar period speak of long days at the beach, tea dances, and endless rounds of cards. Travel between the two cities was so easy that many men would spend the week attending to business in Cairo and then travel to Alexandria to join their family for the weekend.

The Jews of Baghdad had to travel a bit further to reach the Mediterranean, with Lebanon and Palestine being their main summer destinations, and at times also jumping-off points for more exotic travel. With no train connecting Baghdad to Beirut, the bus was the most popular form of transport. Run by the New Zealand–born Nairn brothers, who served in the Middle East during World War I and never left the region, the Nairn Transport Company ran a bus route (which also acted as a postal delivery service) originating in Baghdad, with stops in Damascus, Beirut, and Haifa, after which it was possible to board a taxi, train, or boat to reach one’s final destination. The Nairn buses were so popular that already in 1925 Rachel Ezra, a Baghdadi Jewish socialite from Calcutta, recounted the ease of travel during her Grand Tour of the Middle East, producing a piece for the Iraq Times titled “From Damascus to Baghdad: A trip across the Syrian Desert.” Like their Baghdadi brethren, Jews in Mandate Palestine also headed to the cool mountains of Lebanon to relax under its famous cedar trees, an antidote to the stifling humidity of summer in Tel Aviv. In fact, the Palestine Post issue of August 29, 1934, ran an article with a title we would be prone to initially misconstrue today, though its subtitle makes its meaning clear: “Palestinians Invade the Lebanon: Jews Are Majority among Holiday Makers,” stating that Beirut reported all-time record highs of Jewish tourism, possibly due to publicity campaigns in neighboring countries. The article also mentions an increase in Lebanon’s traffic caused by the influx of tourists, which also sounds like my experiences in the South of France in summer!

Although private correspondence and memoirs point to Lebanon as the preferred holiday destination of Levantine Jews due to its cool climate, Mandate Palestine was also a popular destination. Palestine had the added advantage of the option to make a pilgrimage to Jerusalem and other holy sites, and potentially practice one’s Modern Hebrew if so inclined. Naturally, leisure tourism was not the only motivation for the Jews of the Middle East to explore their region. The archives are replete with examples of medical tourism to consult specialists, salesmen embarking on long trips to expand their commercial networks, and, of course, visits to family and friends who had moved abroad driven by economic opportunity or marriage. As I read these travel logs, I am reminded how geographically small the region is and how easy travel once was.

These travel anecdotes are a reminder of the high level of Jewish participation in Middle Eastern leisure society and the permeability of borders prior to the creation of the State of Israel. Jewish travelers were a specific, and often recognizable

demographic, as attested by the aforementioned newspaper headline. Furthermore, from the perspective of leisure, both members of historic Jewish communities in the region and newer European arrivals to Palestine were grouped into the same

demographic. Interestingly, these leisure travel patterns persisted in parallel to mounting political tensions surrounding Jewish political aspirations in Palestine. For example, in the late 1930s, amid the Arab revolt in Palestine and heightened

political tension in Iraq, it was completely plausible for Jews from Baghdad and members of the new Yishuv to find themselves together at a summer resort in Lebanon. Just as many continue to travel for leisure during the current pandemic,

Jews continued to travel throughout the Middle East even as political tension grew.

So, as I sit here at my desk, dreaming of summer holidays in the South of France, I not-so-very-secretly hope that one day I can be like the Jews of the Middle East that I study, who could pack their suitcases and travel from Baghdad or Cairo to Alexandria or Tel Aviv for a few weeks of holiday without thinking twice. In this long pandemic period in which travel seems to be becoming more complicated, and the Arab world more polarized, I remain optimistic that perhaps one day I will be able to organize my own Middle East road trip. Beirut to Alexandria is only 1300 km by car, the same distance as the Hague to Nice. Just think of all of the great stops that could be made during such a journey!

Sasha Goldstein-Sabbah is assistant professor at the University of Groningen in the Netherlands, specializing in the modern history of Jews from the Middle East and North Africa. She is the author of Baghdadi Jewish Networks in the Age of Nationalism (Brill, 2021).