Above: Ken Goldman. Jacob’s Ladder Triptych, 2015. Chromaluxe print after performance. Photos by Gideon Cohen

Between the late eighteenth and mid-twentieth centuries, several thousand Jewish books were published with lists of presubscribers (or prenumeranten), in a practice similar to today’s crowdfunding campaigns. Though the lists are generally organized alphabetically, either by name or by place, sometimes the order is geographical. By plotting such lists on a map, it is possible to reconstruct the journeys that authors or their agents took as they sold subscriptions to their books. A look at three examples will shed light on different aspects of this intersection between the world of travel and the world of books.

The Failed Magnum Opus

Rabbi Shalom Lukianovsky had ambitious plans when he began writing Yad shalom, a running commentary on Shulḥan ʿarukh, around 1890. Though situated in the tiny southern Ukrainian village of Flora, he garnered approbations from a dozen leading rabbis—Ashkenazic and Sephardic, Hasidic and Mitnagdic—from across the Pale of Settlement, from Kovno to the Crimea, and even one from Galicia. Alas, when, in 1910, he published the first sixty-odd pages of his magnum opus, which he estimated to be over 6,000 pages, it failed to resonate among readers.

Partial page of subscribers to Shoresh Yishai from Subcarpathian Ruthenia, in today’s Ukraine. Courtesy of the author

Undeterred, two years later he published Mefaʿaneaḥ neʿelamim, a work that had broader appeal, with the hopes that income from the second book would fund the publication of his voluminous masterwork. By mapping the list of presubscribers we see that he undertook at least six different trips, visiting about eighty towns in Bessarabia (roughly today’s Moldova) and southern Ukraine. We also identified his method: Starting from Chubivka Station, near his home, he would take the train to a new locale and travel around to nearby Jewish communities.

Despite his massive efforts, Yad shalom never caught on. The one printed volume has been all but forgotten by students of Halakhah, and no trace of the massive manuscript remains.

Map generated using data from the Prenumeranten Project and HaMapah. Courtesy of the author.

The Book of Compassion

The biblical book of Ruth is known for its account of incredible acts of kindness and mercy. Its tale of the redemption of a foreign-born widow sets the stage for the flourishing of the Kingdom of Israel under David and his line.

In the late 1800s, a young man named David Shmuel Katz of Felsöneresznicze, Hungary (today’s Novoselytsya, Ukraine), decided to reissue Shoresh Yishai, a commentary on Ruth by Rabbi Shlomo Alkabeẓ, first published in Constantinople in 1561. Katz’s edition was published in Sighet (Sighetu Marmației, Romania) in 1891, with an astounding thirty pages of presubscribers. What accounts for the improbable success of this edition?

It turns out that David Shmuel Katz tragically passed away while putting the finishing touches on his edition, leaving his wife, Nisl Gitel, a widow, and four young children orphans.

Nisl Gitel’s brother, Ẓvi Elimelekh Naiman, undertook to complete the edition and then to sell the book, with the proceeds going to support his sister and her children.

In all, he visited close to five hundred different places in what was then northeastern Hungary (Unterland), today

in Hungary, Slovakia, Romania, and Ukraine. He undertook seven or eight different journeys, visiting large towns as well as villages

that now lie beneath reservoirs created by Soviet-era damming projects. The people responded by turning this edition into a bestseller.

This intersection of a particular book, a series of journeys, and the response of an audience whose compassion was aroused provides a worthy coda to the book that set this process in motion, the book of Ruth.

These interactions, and perhaps a bit of luck, determine whether a book … remains unpublished or becomes an unexpected bestseller.

Cultural Bridging and Wanderlust

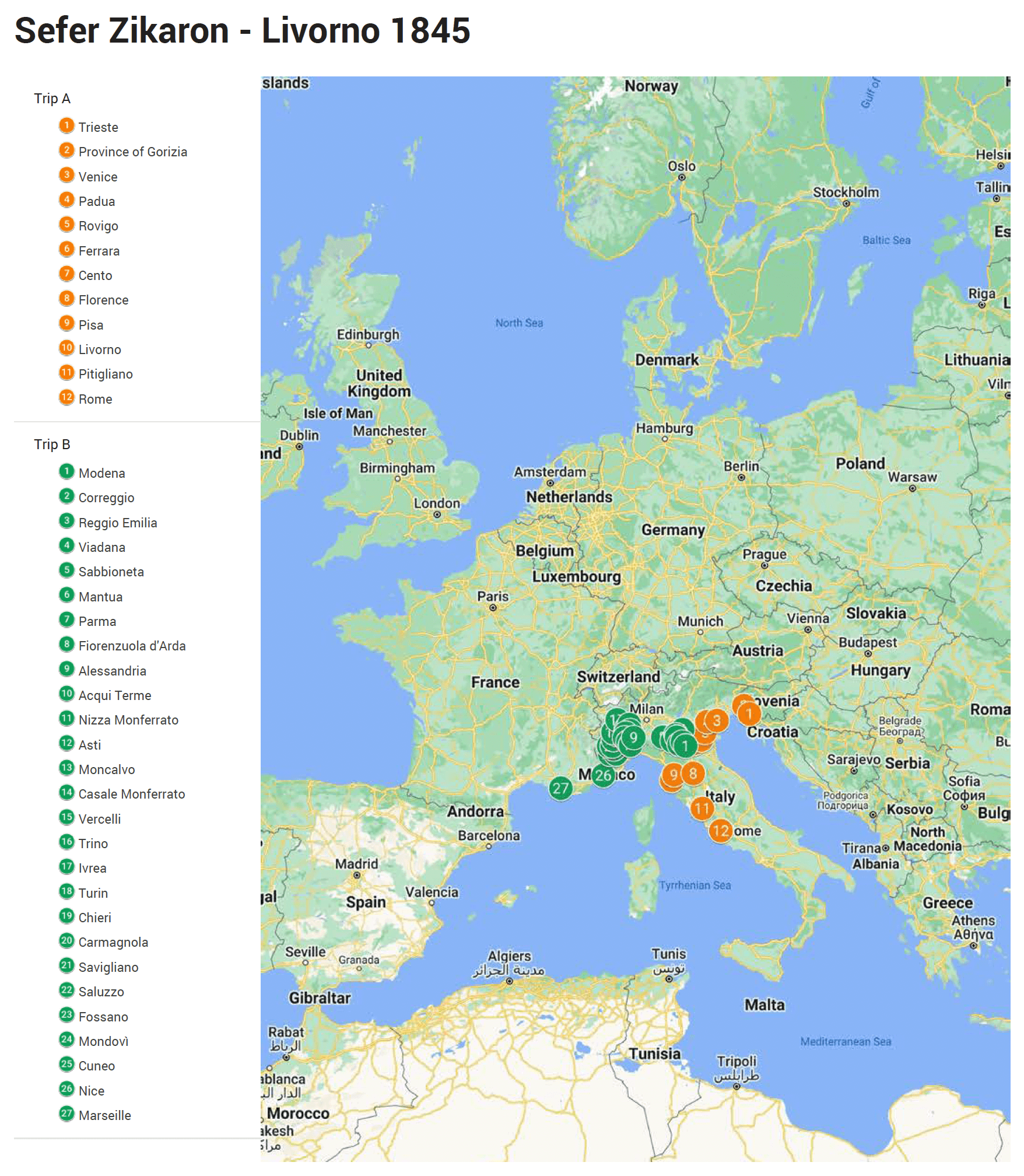

Eliezer Ashkenazi was born in Poland in the early nineteenth century, but in 1845, his home was Tunis, and he was on his way back to Europe, to publish a manuscript he found in North Africa. He had become a collector, dealer, copyist, and publisher of such manuscripts, and he returned to Europe several times, and by several different routes, writing on one occasion of his travels to Gibraltar by way of Morocco, and on another occasion of his return to North Africa from the port of Marseille.

As can be seen from Ashkenazi’s introduction to the first work he published, Sefer zikaron (Livorno, 1845), by an early sixteenth-century Spanish refugee rabbi who found his way to Tunis, Ashkenazi viewed himself as a cultural bridge between the different lands of his travels.

For the past ten years, it has been my delightful lot to help the elect of the human race, to be a deliverer and courier of all kinds of books, old and new, from Sepharad to Ashkenaz and from Ashkenaz to Sepharad. No distance was too

great for me. The dry heat of Africa did not stop me, and the ice of Ashkenaz did not deter me. …

I witnessed the wisdom of Ashkenaz rejoicing in the courtyards of Sepharad, and the sagacity of Sepharad raising her voice in the streets of Ashkenaz—and it was from me. I brought it about. Though I ate bread in misery, this legacy is more beautiful to me than the legacy of traders in gold and jewels. …

Sweeter to my palate was dry bread dipped in stagnant water in the bowels of a ship and bread, dates, and water from a skin on a dune in the Arabian desert than every delicacy of kings and princes.

Ashkenazi complains of the difficulty of traveling, but there is no doubt that travel was part of the attraction

of his chosen lifestyle. Indeed, between 1845 and 1855, he published three volumes of treatises, letters, liturgical compositions, and commentaries, each in a different European city: one in Metz, one in Frankfurt, and one in Livorno. Each work has a list of subscribers, but, incredibly, he never visited the same place twice! One journey took him to forty Jewish communities in (mainly northern) Italy. Another began in Paris but brought him to almost one hundred communities in Alsace and Lorraine.

Conclusion

During the modern era, thousands of individual Jews took to the road to sell their books, and it is rare that we are able to glimpse their thoughts and motives as they traveled from place to place. In the handful of examples discussed here, we see travelers spurred by compassion for family, the desire to absorb and cross-pollinate different regional Jewish cultures, and the conviction that they have penned a significant halakhic work that must be published. We have also seen how travel intersects and interacts with others aspects of Jewish culture: book culture, intellectual culture, and the culture of charity. These interactions, and perhaps a bit of luck, determine whether a book, even one born of great ambition, remains unpublished or becomes an unexpected bestseller.

ELLI FISCHER is a researcher with the Prenumeranten Project and HaMapah (hamapah.org), affiliated with Haifa University and the University of Wroclaw.