Above: Detail from Archie Rand. 326: To Send the Impure from the Temple (Numbers 5:2), 2001-2006. From the series The 613. Acrylic on canvas. 20 x 16 in. Photo by Samantha Baskind

Artists on Their Art

Richard McBee. Rabbi’s Maid, 2016. Oil on canvas. 30 x 40 in.

Amid the flurry of misogyny in the Talmud tractate Ketubot, one encounters the singular story of the death of Rabbi (Rabbi Judah ha-Nasi, the editor of the Mishnah). We can well appreciate the talmudic authors’ distress at relating the death of the literary and spiritual leader of their rabbinic revolution, that is, the first written codification of the Oral Law. His death signaled the end of an era.

On page 104a, his death looms and everyone wants to postpone this inevitability; so much so that it was decreed forbidden to even mention his demise when it actually occurred.

Deeply distressed, Rabbi’s maid ascended to the roof and prayed: “The angels desire Rabbi to join them and his students desire Rabbi to remain with them; may it be the will of God that his students may overpower the angels.” When, however, she saw how often he resorted to the toilet, painfully taking off his tefillin and putting them on again, she prayed: “May it be the will of the Almighty that the angels may overpower the students.”

And yet the students incessantly continued their prayers for him to live; so she took matters into her own hands. She carried a large jar up to the roof and threw it down to the ground with a loud crash. Startled for a moment, they ceased praying and the soul of Rabbi departed to its eternal rest.

What an amazing story of the courageous action of one woman, confounding the rabbinic elite and assisting in the mercy death of the greatest sage of the time! This story simply demanded to be addressed in visual art.

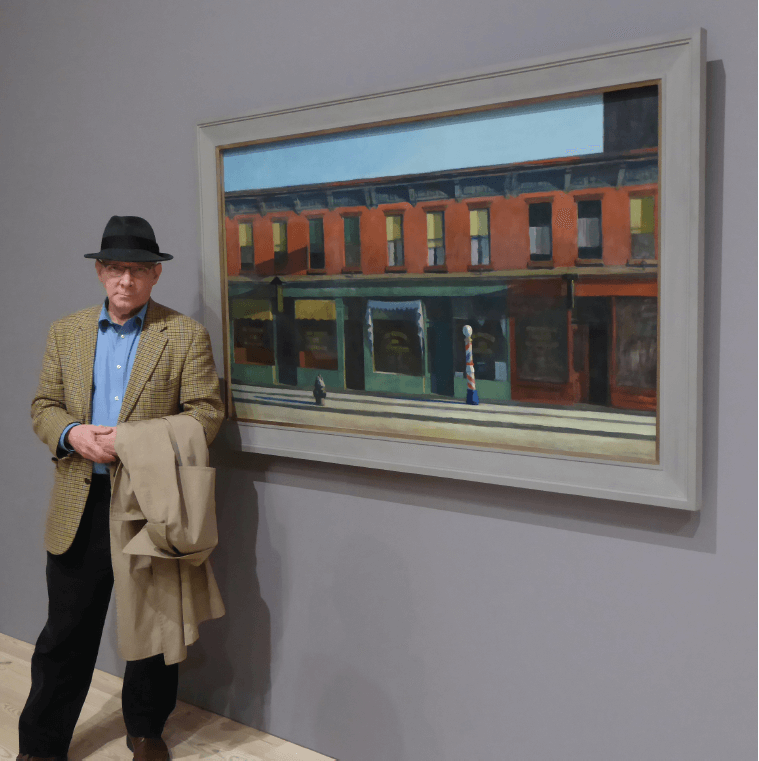

Edward Hopper’s Early Sunday Morning at Whitney Museum in situ with McBee. Photo by Menachem Wecker

It seemed to me that the images of Heaven above would have to be contrasted with the earthly petitioners below, perhaps all in a yeshiva or beit midrash setting. Considering my own experience as a yeshiva student at Mesivta Tiferes Jerusalem on the Lower East Side of Manhattan, an urban storefront might work well to allow the viewer to look in and see the students studying and praying for the merit of their master.

A building with a second floor would allow depicting the sick Rabbi in bed in a room upstairs. So I simultaneously started sketching options and also looking for an art historical model to appropriate that would refl ect the narrative setting and transform it into something contemporary.

The tranquil peace of Hopper’s scene psychologically set the drama about to unfold.

One of Edward Hopper’s most famous images, Early Sunday Morning (1930), was perfect for this narrative. The tranquil peace of Hopper’s scene psychologically set the drama about to unfold. The talmudic story progressed relentlessly; the holy Rabbi was dying! The desperate students, those who knew him and even those who had simply heard of this great master, have gathered in the storefront yeshiva to do whatever they could to allow this eminent man to live a bit longer. All night they studied Torah in his merit and prayed to avert the inevitable death that approaches … and dawn comes, quietly and beautifully … Early Sunday Morning.

And then suddenly—this unnamed woman, a loyal maid of a holy man—takes action! The talmudic narrative driven by an antinomian feminist perspective in combination with an appropriated image guarantees instant visual recognition for an otherwise unknown subject.

Executing the painting involved multiple adjustments to the original, including the addition of an elderly couple out for a morning stroll. Turning back, they have just noticed the praying yeshiva students and the women’s minyan, unaware of the flying jug about to shatter the morning quiet.

Not surprisingly, images sometimes summon unanticipated reactions and responses. Within a year of its creation, a colleague of my daughter, Dr. Moshe Cohn, saw this painting on my website and immediately bought it, since it depicted perfectly one of the main aspects of his philosophical and practical approach to palliative care.

His rabbi, Rabbi Moshe David Tendler, a noted expert in Jewish medical ethics, frequently uses this specific talmudic passage imaged in my painting as additional textual support to his halakhic position that, in a case of someone who is dying and suffering but is prevented from dying by some agent or process, it is permissible to remove that agent to allow the person to peacefully die. Since normally Jewish law forbids any action that could hasten an individual’s death, this is not accepted by all halakhic authorities. Nonetheless Rabbi Tendler’s position emphasizes the elimination of suffering (i.e., quality of life) to be a crucial mitigating factor. Rabbi’s maid in the Talmud clearly took this merciful position and my painting firmly brings its perspective into the twenty-first century.

.

RICHARD MCBEE is a painter of biblical subject matter and writer on Jewish art. He is a founding member of the Jewish Art Salon. His artwork and reviews can be seen at richardmcbee.com.