Above: Detail from Archie Rand. 326: To Send the Impure from the Temple (Numbers 5:2), 2001-2006. From the series The 613. Acrylic on canvas. 20 x 16 in. Photo by Samantha Baskind

Artists on Their Art

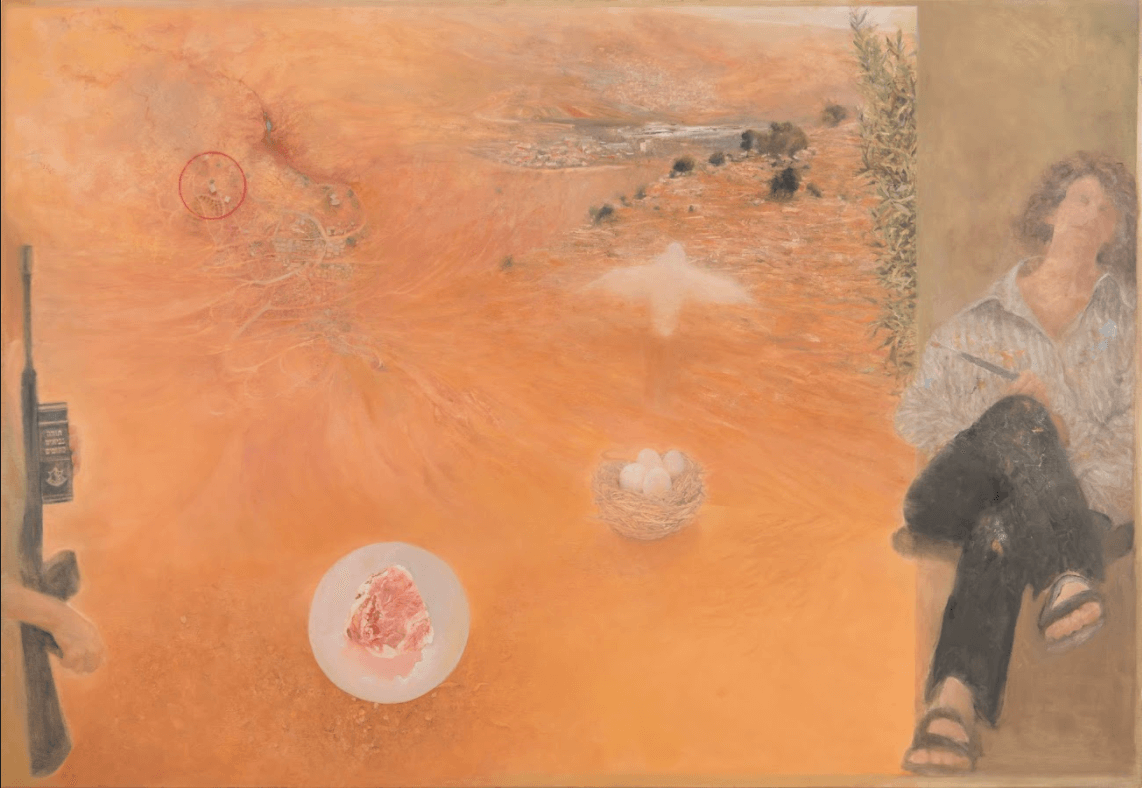

Ruth K. Ben-Dov. Ki Tetzeh (When you go out to war), 2015. Oil on canvas. 39 x 57 in. Photo by Dror Miler

May 19, 2021

The image of the sleeping artist at right hints at the dreamlike quality of the landscape that takes up most of this large painting. This scene includes a visual conversation with the Torah portion Ki Teẓe’, which opens with the laws of war: “When you go to war against your enemy …” (Deuteronomy 21:10). I was spurred to paint it when three of my four children were serving in the Israel Defense Forces at the same time. This led to my attending a number of military ceremonies in close succession. Even though I served in the IDF, these events appeared strange to me, and thus a combined insider- outsider view lies at the heart of the painting. My ambivalent outlook goes beyond the struggles of any Israeli parent, as I carry within me childhood memories of attending antiwar demonstrations with my parents in Washington, DC, where I was born. Writing here about the painting invites me to ponder that upbringing, as well as the decision to make Israel my home.

In the painting I become that mother bird, flying away and leaving the eggs to be removed.

Much of the imagery in the painting connects seemingly unrelated sections of the Torah portion to its opening. This includes the law of sending the mother bird away before taking her eggs or chicks, usually interpreted as an act of compassion (Deuteronomy 22:6–7). In the painting I become that mother bird, flying away and leaving the eggs to be removed. Looking at those four sweet eggs, I appreciate their deep connection to our nest and their commitment to protecting it. Incidentally and ironically, the soundtrack in many IDF ceremonies includes a popular Israeli song with the refrain “Fly away, chick!” sung by a mother bird to her offspring.

In a key ceremony my children promised to defend our country, even at the cost of their lives, while holding a Tanakh (Hebrew Bible) in one hand and a gun in the other, the two joined in an act of salute. The female figure enacting that moment at the left edge of the painting brings to mind another law from the Torah portion, the prohibition against a woman wearing male attire (and vice versa, in Deuteronomy 22:5). Here the gun is the ultimate male attire, in my daughter’s hands. After returning home from one of the swearing-in ceremonies I cooked a Shabbat meal. Looking at a raw piece of chicken in my kitchen brought to my mind the bloody reality hidden behind both our appealing cooked food and our uplifting military ceremonies. I recognize that violence is a human reality, as does the Torah, with its laws of war and eating tempering that reality, rather than denying it; thus the shocking union of gun and Bible makes sense. Still, I look back at those childhood antiwar demonstrations and wish they hadn’t failed.

While working on this painting I allowed myself to proceed without detailed planning, allowing visual surprises to emerge: the landscape seems to fold into itself and change perspective, from the view from my studio balcony overlooking the Galilee hills (with the Jewish and Arab towns of Karmiel and Deir El-Assad) to an aerial view of an imagined site seen from a plane. This site is targeted with a red circle and bears the shadow of a fighter plane. The circular target resonates with the circular plate holding the piece of chicken, as well as with the circular nest. That piece of chicken, a dead bird, leads the eye to its counterpart, the flying one, with the shadow of the aircraft creating a visual triangle between the three. The interplay of colors includes the golden earth tones that take up much of the canvas, punctuated by the white plate, bird and eggs, red target and meat, and framed at left and right by the green of uniform and olive tree. The paint itself is of course what creates the illusion of space and volume, while its texture becomes the texture of the rocky land; yet it also stands for itself, as stains of paint covering the sleeping artist’s work clothes. Thus the visual experience of the work is the fundamental conduit to its ideas, reflecting my ambition to fuse observational painting with explorations of place and identity.

As I write this piece, my youngest son is on active duty on the Gaza border. While Ki Teẓe’ reacted to military ceremonies and training, now it’s the real thing. And as the painting doesn’t reconcile the chaotic imagery within it, so I learn to live with the various voices within me: the fear of losing a child to war and the sadness about the children killed by our forces; the acknowledgement that I have enemies who want to eradicate me, my family, and my people, and the hope for reconciliation with my Arab neighbors here in the Galilee.

Note: The painting Ki Tetzeh was inspired by an earlier work on parchment that was part of the Women of the Book project (www.womenofthebook.org).

RUTH KESTENBAUM BEN-DOV is an artist living in Eshchar in northern Israel. Her work is featured in exhibitions devoted to Israeli painting and contemporary Jewish art. Website: www.ruthkben-dov.com