Above: Detail from Archie Rand. 326: To Send the Impure from the Temple (Numbers 5:2), 2001-2006. From the series The 613. Acrylic on canvas. 20 x 16 in. Photo by Samantha Baskind

PEDAGOGY ROUNDTABLE

Sponsored by the Holocaust Educational Foundation of Northwestern University

Introduction

Sarah Cushman: The Holocaust has stimulated inquiry in a range of disciplines, and methods and approaches used in these disciplines have broadened our understanding of the Holocaust. This development has grown Holocaust Studies from its base in History into a multi- and interdisciplinary field. Art and Art History have been late to embrace the study of the Holocaust. Adherents to traditional aesthetic hierarchies in those disciplines have long asserted there was no “art” produced under the Nazi regime, and have viewed visual culture of the era as documentary evidence, not the subject of serious artistic inquiry. At AJS 2020, held online, the Holocaust Educational Foundation of Northwestern University sponsored a roundtable on “Teaching the Holocaust through Art.” Panelists explored debates and recent developments in Art and Art History, and shared approaches, sources, and tools they use for teaching about the Holocaust.

Barbara McCloskey: Reckoning with the effects of images is critical to understanding the Holocaust and how it unfolded. Students in my course on art in the Third Reich and the memorialization of the Holocaust explore how visual media cemented the Aryan ideal of “German-ness” to oppress and eliminate Others— Jews, homosexuals, and the differently abled. The course exposes students to a range of visual media—painting and sculpture, film and exhibitions— to examine dialogically how structured absence, particularly of Jews, served to picture and create a Volksgemeinschaft (German people’s community).

For analysis of architecture, I use my fellow panelist Paul Jaskot’s The Architecture of Oppression, which helps students to consider the regime’s architecture in more than simply formal or stylistic terms. Students are asked to contemplate the relationship between war production minister Albert Speer’s use of modernism and classicism in his design of the Reich Chancellery, and the “Stairs of Death” at Mauthausen concentration camp, where those forced to hew stone for the structure were worked to death. Jaskot’s book exposes how Nazi building policy forwarded the processes of dispossession, ghettoization, and extermination.

I also use Images in Spite of All by philosopher and art historian Georges Didi-Huberman. The text helps students understand how disciplinary notions of “art” can prevent us from seeing and taking seriously the testimony that unremarkable visual materials can yield. The author’s brilliant analysis of four fragile, astonishing, and long-overlooked photographs of mass killing at Auschwitz demonstrates to them what Art History at its very best can do.

Sonderkommando photographs taken secretly by prisoners in KL Auschwitz II-Birkenau, Summer 1944. The photos show burning bodies and women being driven to gas chambers in Auschwitz IIBirkenau. Auschwitz-Birkenau State Museum. www.auschwitz.org

When dealing with the postwar period, I ask students to explore the destruction of the image world by the Nazi regime and the ensuing challenge to create a visual language adequate to memorializing the Holocaust. The work of James Young is especially useful here. Students explore how memorials seek to remind us of the murderous legacy of the Holocaust and warn us against recurrences of cultural intolerance.

Finally, connecting students’ historical study of the Holocaust to the present, I discuss with them the dark web and its veiled adoption of Nazi imagery. Students contend with how and why that imagery morphs and goes viral, and they consider to what extent it works to shape identity today in ways similar to how visual culture functioned in the Third Reich.

Suggested Reading List:

Georges Didi-Huberman, Images in Spite of All: Four Photographs from Auschwitz (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2008).

Paul B. Jaskot, The Architecture of Oppression: The SS, Forced Labor and the Nazi Monumental Building Economy (New York: Routledge, 2000).

James E. Young, The Texture of Memory: Holocaust Memorials and Meaning (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 1994).

Belarie Zatzman: My disciplinary approach to teaching the Holocaust through art-making practices is grounded in Theatre and Performance Studies. Scholar James E. Young posited that “the facts of history never ‘stand’ on their own—but are always supported by the reasons for recalling such facts in the first place” (Young, Stages of Memory, 98). Young asks us to consider why we are doing this work with our students. We must remain acutely aware of the critical and aesthetic relationship between content and form, and recognize that “what we choose to tell, to whom we choose to tell it, and indeed, how we choose to tell it, all matter” (Zatzman, 97) .

Young’s reflection—that “the most important ‘space of memory’ is not ‘the space in the ground’ or above it but the space between the memorial and the viewer, between the viewer and his or her own memory: the place of the memorial in the viewer’s mind, heart, and conscience” (Young, Memory’s Edge, 119)—impacts how I structure my curriculum. The performance of memory, the obligation to witness, and the representation(s) of narratives of identity are critical to my design of arts-education projects.

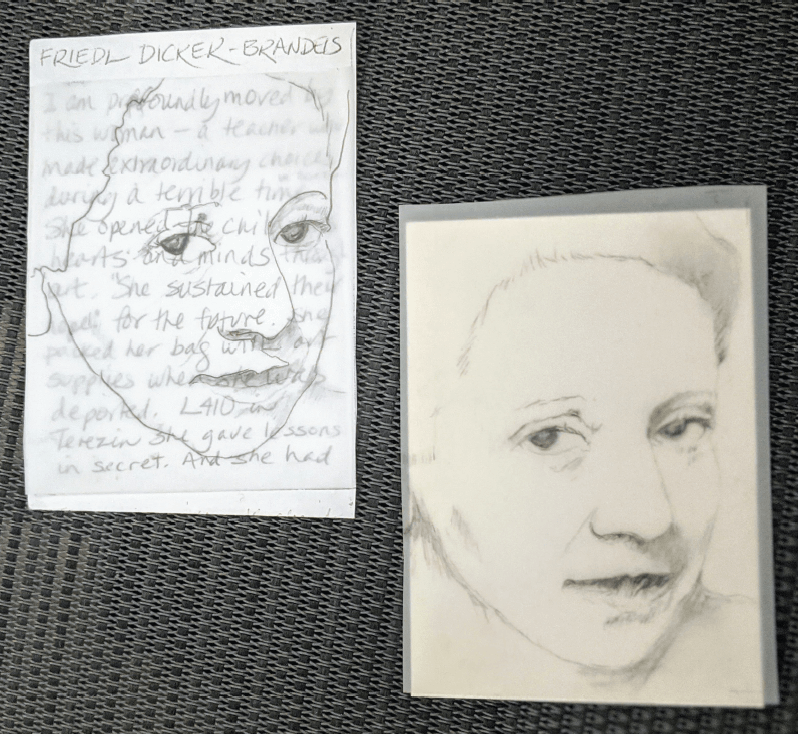

Artist Trading Cards (ATCs) are miniature artworks meant for exchange. They offer artistic opportunities for response to and reflection on the Holocaust. This ATC responds to the play, Hana’s Suitcase by Emil Sher. It depicts a drawing of Friedl Dicker-Brandeis (1898–1944), the remarkable Bauhaus artist, who taught children in the Terez n ghetto. The participant created this sketch of Friedl on transparent mylar, evoking Charlotte Salomon’s work. Beneath the portrait, the handwritten text suggests the deep impact of Hana and Friedl’s narratives on the student.

Theatre historian Scott Magelssen asks us to consider the position of the audience/viewer not only as receivers of content, but also as cocreators. He cautions against passively consuming historiographic narratives. Literature scholar Adrienne Kertzer argues that “why people attend theatre about historical atrocity and what they do after the performance are what matters” (Kertzer, vii). Consequently, I attend to the extended spaces of performance— to the work that happens before and after seeing a piece—as I shape pedagogical encounters. Through pre- and post-show programs, we help teachers/artists/ students address the Shoah’s rupture across generations, audiences, and contexts.

Educational drama and applied theatre offer participants a “framework for responding” (Langer, 12) to the difficult knowledge of the Shoah through real and imagined contexts. Possibilities for designing artistic and educational materials that respond to the Shoah include monologue and scene-study work; movement; poetry; visual arts; artist trading cards; photographs; and artifacts and memorials. Multidirectional and participatory practices— and knowing who is in the classroom—invite multiple perspectives and offer opportunities for reflection on and creation of their own responses to the Shoah. These forms of representation engage the lived experiences of participants to support their sense of agency and shared authority in remembering and re-telling the Holocaust through art.

Suggested Reading List:

Adrienne Kertzer, My Mother’s Voice: Children, Literature, and the Holocaust (Peterborough, ON: Broadview Press, 2002).

Lawrence Langer, ed., The Holocaust and the Literary Imagination (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 1975).

Scott Magelssen, Simming: Participatory Performance and the Making of Meaning (Ann Arbor, MI: University of Michigan Press, 2014).

James E. Young, At Memory’s Edge: After-Images of The Holocaust in Contemporary Art and Architecture (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 2000).

James E. Young, The Stages of Memory: Reflections on Memorial Art, Loss, and the Spaces Between (Amherst: University of Massachusetts Press, 2016).

Belarie Zatzman, “Staging History: Aesthetics and the Performance of Memory” in The Journal of Aesthetic Education 39, no. 4 (Winter 2005): 95–103.

Natasha Goldman: Overlooked monuments often disclose a commissioning body’s wish to obscure information while well-known, provocative memorials point to a community’s readiness to address difficult pasts.

When teaching students and teachers (the latter as part of the NEH Summer Seminar for School Teachers, “Teaching the Holocaust through Visual Culture”), I empower students with little historical knowledge to concentrate on what they see, thereby prompting them to interpret details and ask questions. For instance, Charlotte Salmon’s Life or Theatre? (1940–42) is an autobiographical work of small-scale watercolors that depict the rise of Nazi power and the artist’s adolescent anxieties and family suicides. The latter address themes students understand, helping them see Jews not solely as victims, but as people with everyday problems. Micha Ullman’s Bibliothek (Berlin, 1995) is a small, underground memorial of empty bookshelves and is a respite from horrific, sometimes seductive Holocaust imagery. Will Lammert’s Monument to the Deported Jews (Berlin, 1957/1985) was originally part of the Ravensbrück concentration camp memorial, but the commissioning body deemed it too “unheroic” for that site. East German art theory and Holocaust memory from the 1950s to the 1980s play vital roles when interpreting this memorial.

Will Lammert, Memorial to the Victims of Fascism, Berlin, 1985. Originally designed in 1957 for the Ravensbrück memorial (never installed; known as The Unfinished). Installed in 1985, Große Hamburger Straße, by Mark Lammert. Also known as the Monument to the Deported Jews. Bronze. Photo by Jochen Teufel

I conclude my Holocaust courses with works that demonstrate how the Holocaust matters today. British architect Sir Normal Foster’s Reichstag cupola dome (2005) offers a metaphor for transparency and democracy. Hans Haacke’s To the Population (2000), in the Reichstag’s courtyard, converses with the phrase “to the German people,” chiseled on the exterior of the Reichstag, pitting the attitudes of those who oppose immigrants, guest workers, and asylum seekers against those who recognize the entire population—citizens and noncitizens—as worthy of representation.

Such works of art and memorials have the potential to enrich pedagogy about the Holocaust not only in the Art History classroom, but also in literature, film, history, foreign language, or Jewish Studies.

Suggested Reading List:

Natasha Goldman, Memory Passages: Holocaust Memorials in the United States and Germany (Philadelphia: Temple University Press, 2020).

Michael P. Steinberg and Monica Bohm-Duchen, eds., Reading Charlotte Salomon (Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 2006).

Chen Tamir, “Hans Haacke,” in Entry Points: The Vera List Center Field Guide on Art and Social Justice, no. 1, ed. Carin Kuoni and Chelsea Haines (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2015), 112–17.

Paul Jaskot: Most scholars approach the topic as “the Holocaust AND art”: art is supplemental, not central. How can we teach the Holocaust through art? I taught my first “Art & the Holocaust” seminar in 1995, when scholarship from art historians was thin. The literature has proliferated and now includes contributions on architecture, painting, design, and sculpture.

Research on Holocaust-related art can prompt discussions of Jewish experience and the perpetrator’s antisemitic policy in complex relational terms. We can push students to think about both in new ways through the same object, event, or cultural experience.

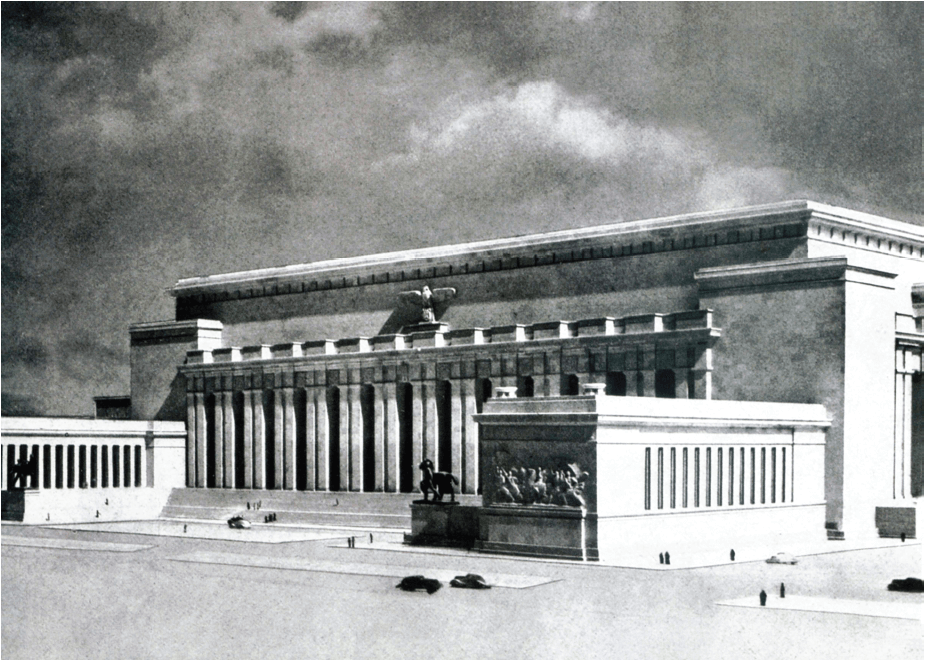

William Kreis. Soldier’s Hall, Berlin, 1938. Photo by Reinhard Schultz. Prisma by Dukas Presseagentur GmbH / Alamy Stock Photo

We can demonstrate such an approach using architect Wilhelm Kreis’s Soldiers Hall (begun 1938), planned as part of the rebuilding of Berlin. At first glance, Soldiers Hall seems a typical Nazi building: a monumental neoclassical structure doing what we expect propaganda to do. But why did the perpetrators see this as a culturally positive monument? On the one hand, the massive scale and the eagle over the door reference the Roman Empire, revealing the imperial fantasy that characterized 1938 Germany. On the other, the layout of the building references the Greek Pergamon Altar, signaling ideological notions of racial lineage and superiority. The process of unpacking these references reveals fundamentals of perpetrator ideology—how Nazis thought about imperialism and race in co-equal terms.

The scale of the plan of which the building was a part (one-third of Berlin was to be razed) opens the door to considering Jewish experience. For example, in summer 1938 Albert Speer and his staff developed an antisemitic housing policy to acquire Jewish property for non-Jews displaced by massive site-clearing operations that this and other buildings required. Only In Berlin did Jews register their housing with architects, who used this policy to expedite this project.

Such an analysis reveals the ambivalent history of these objects. They point to the grotesque and inhumane—antisemitism as a racist ideology, as policy and practice experienced by millions of European Jews. They also point to the “positive” role of culture; they show what values perpetrators saw as “good.” Ideology legitimated murder; culture was literally barbaric. Key moments like this point in both directions offering a way to teach an integrated history of the Holocaust through art.

Conclusion

Sarah Cushman: With simple methods and thoughtful planning, monuments, buildings, paintings, and performance can become effective ways to engage students with learning about the Holocaust. The examples above are just some of the ways that instructors can “teach the Holocaust through art.” These examples also illustrate how study of the Holocaust enhances student learning about various Arts and Art History and how those fields and their methodologies contribute to the growth of the field of Holocaust Studies and enrich general understanding of that horrific time.

BARBARA MCCLOSKEY is professor of History of Art at the University of Pittsburgh. Her course, “Art in the Third Reich and Memorialization of the Holocaust,” invites students to study the role of visual culture in identity formation under Nazism.

BELARIE ZATZMAN is associate professor of Theater at York University. She grounds her approach to teaching the Holocaust in Theatre and Performance Studies. She draws upon a range of possibilities for designing artistic and educational materials. Visual culture is inherent to her graduate and undergrad classes.

NATASHA GOLDMAN is research associate in Art History at Bowdoin College. In researching memorials, Goldman uncovers complex, hidden stories and reveals how the Holocaust was understood in different times and locations.

PAUL JASKOT is professor of Art History and Director of the Digital Art History and Visual Culture Research Lab at Duke University.

SARAH M. CUSHMAN is lecturer in the History Department and director of the Holocaust Educational Foundation of Northwestern University.