Above: R.B. Kitaj. Eclipse of God (After the Uccello Panel Called Breaking Down the Jew's Door), 1997-2000. Oil and charcoal on canvas, 35 15/16 in. x 47 15/16 in. Purchase: Oscar and Regina Gruss Memorial and S. H. and Helen R. Scheuer Family Foundation Funds, 2000-71. Photo by Richard Goodbody, Inc. Photo Credit: The Jewish Museum, New York / Art Resource, NY. © 2020 R.B. Kitaj Estate

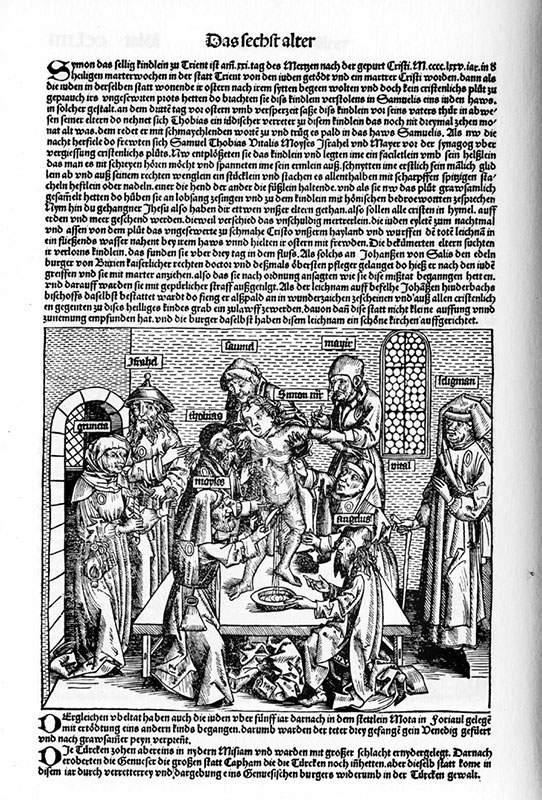

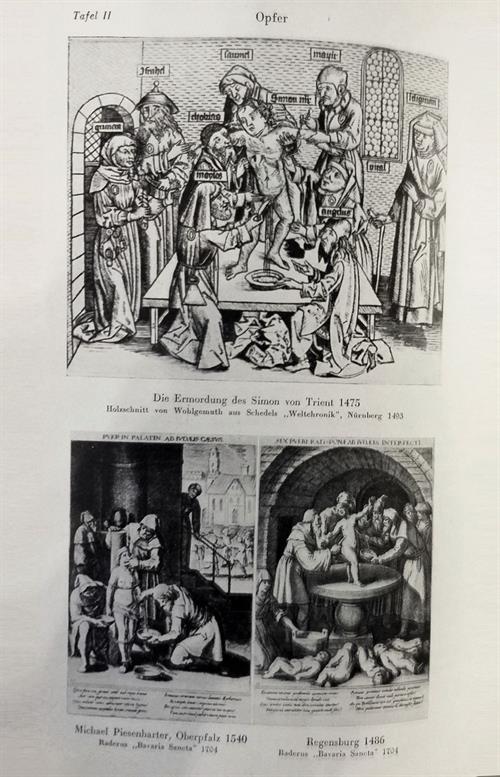

The image of Simon of Trent from Hartmann Schedel’s splendid Weltchronik, or Nuremberg Chronicle, published in Nuremberg in 1493 (254verso), has become one of the most iconic images of ritual murder, embraced as such by both antisemites and scholars. Although neo-Nazis operate in a separate epistemological community, reading and reinforcing their own “authoritative sources” through translations of Nazi publications, including the notorious newspaper Der Stürmer, troublingly, our own work as scholars might be coopted for hateful uses as well. By treating this image as the iconic image of ritual murder, we as scholars may be, unwittingly, affirming its importance in distressing agreement with the (neo-) Nazis. As Sara Lipton has noted, “Texts outlive people who write them, memory of their initial purpose fades, and words take on a new meaning and power”; the same applies to images.i

Simon of Trent in Hartmann Schedel, Weltchronik, or Nuremberg Chronicle (Nuremberg, 1493), 254v

Schedel’s 1493 chronicle was indeed unprecedented, with hundreds of woodcuts of kings, popes, and cityscapes. It included several vivid images of Jews—some of the earliest iconographic representations of Jews in print—with the now iconic image of Simon of Trent as one of the most intricate. The book was magnificent, and very expensive. It thus was not reissued beyond the original 1493 printings in Latin and German.

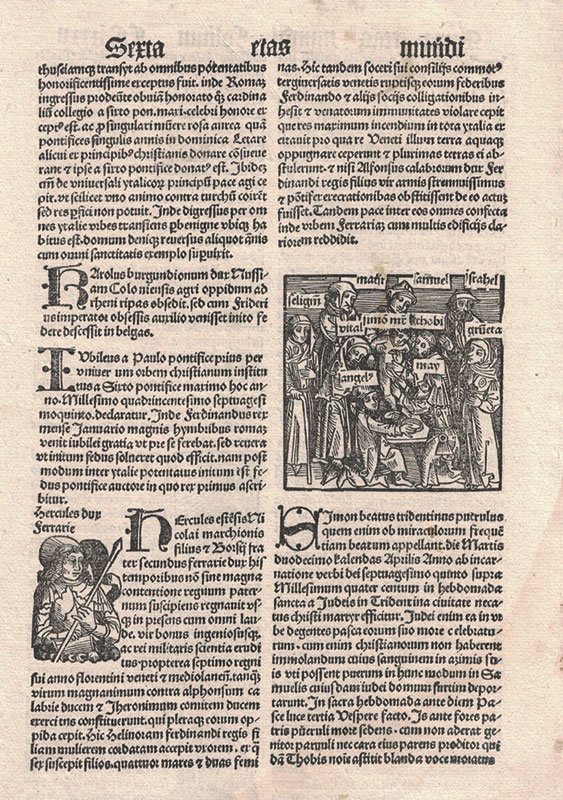

Simon of Trent in the pirated edition of Hartmann Schedel, Liber Cronicarum Cum Figuris et Imaginis Ab Initio Mundi Usque Nunc Temporis (Augsburg, 1497), 285v.

In 1497 a pirated edition—smaller and cheaper—was published in Augsburg, crudely replicating the Nuremberg original (it was then republished in German in 1500 with the same illustrations). The Augsburg edition also had a woodcut of Simon of Trent, a smaller and much cruder mirror version of the one included in Schedel’s Liber chronicarum. But the original 1493 image was never reused in any other publication, nor was widely copied. Indeed, other images were used, reused, and copied in Christian chronicles, but they are now forgotten.

While the now-iconic image from 1493 was not reprinted, or copied, other images of Simon of Trent were used and reused in different countries.

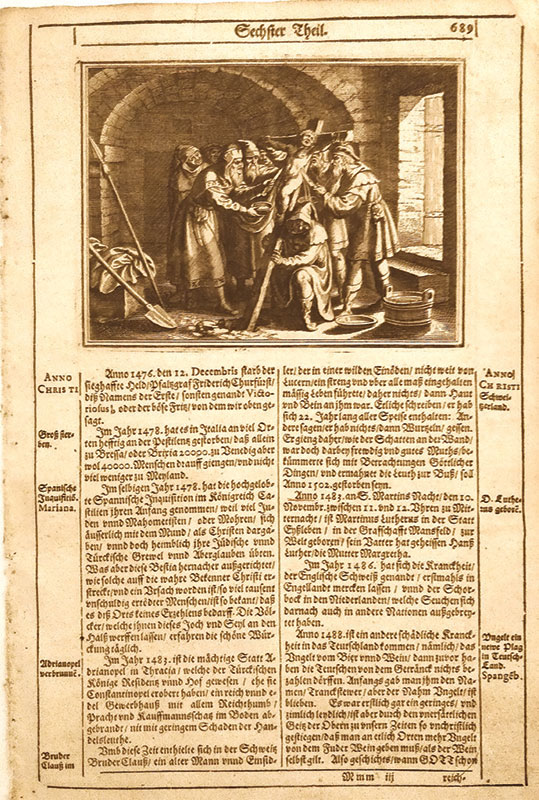

Simon of Trent in Johann Ludwig Gottfried, Historische Chronica (Frankfurt, 1674), 689.

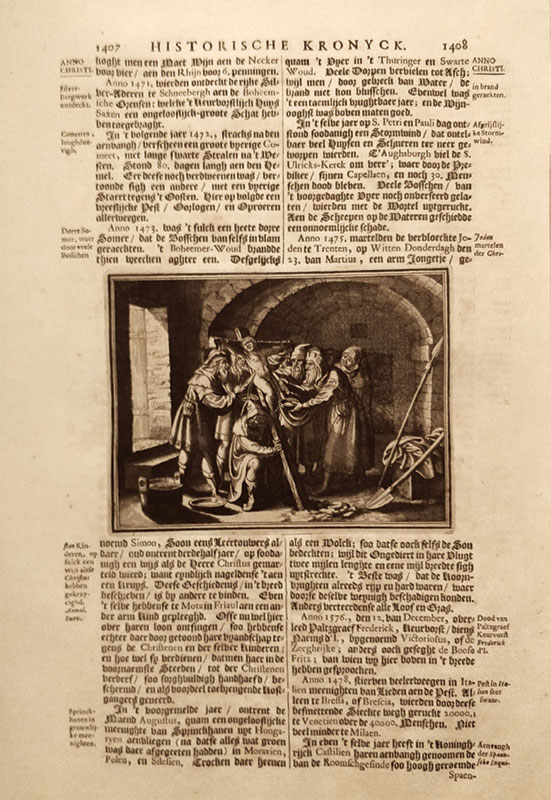

Johann Ludwig Gottfried, Omstandigh Vervolgh Op Joh. Lodew. Gottfrieds Historische Kronyck (Leiden, 1698), 1408.

In 1698 this image was copied in Leiden, and appears as a mirror image in Johann Ludwig Gottfried, Omstandigh Vervolgh Op Joh. Lodew. Gottfrieds Historische Kronyck (Leiden, 1698), 1408.

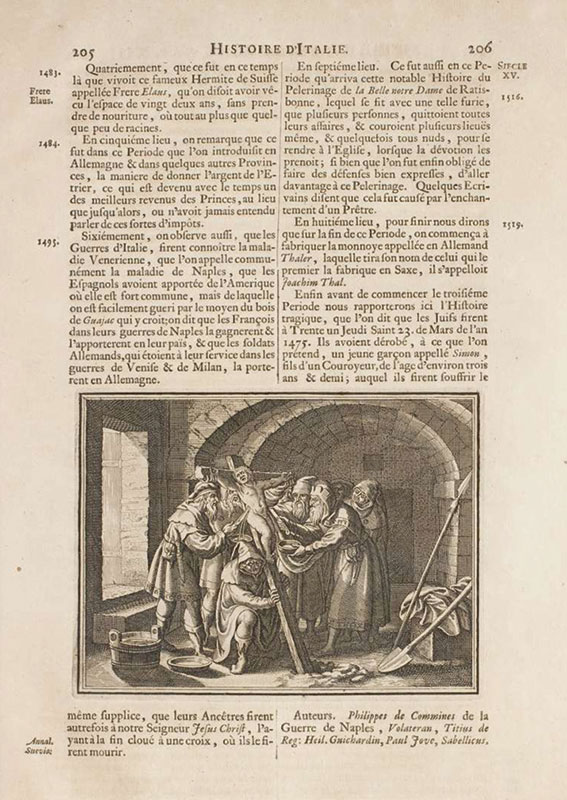

And then in 1704, the 1698 image was reused in Nicolas Gueudeville, Le Grand Theatre Historique.

Simon of Trent in Nicolas Gueudeville, Le Grand Theatre Historique (Leiden, 1704), vol. 4, 206. © http://diglib.hab.de/drucke/gb-2f-11-2b-2s/start.htm?image=00107

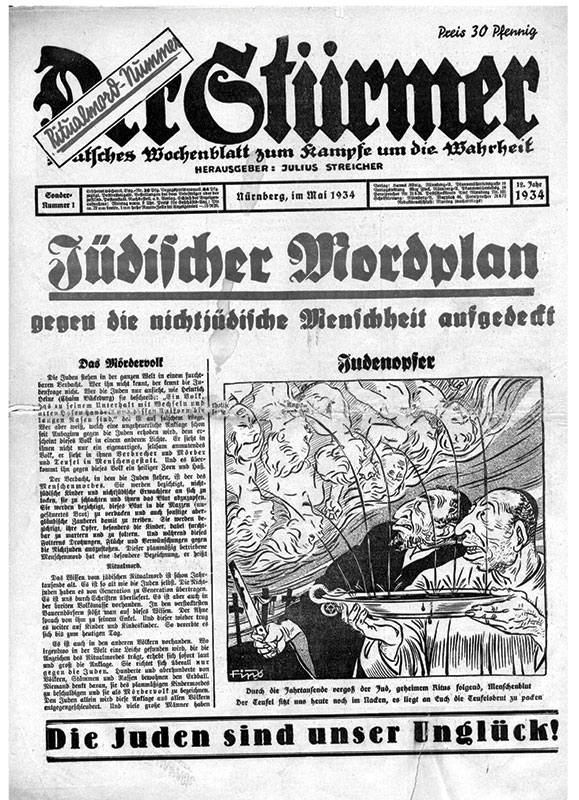

Yet, these representations of Simon of Trent are now forgotten, displaced by the 1493 woodcut from the Nuremberg Chronicle, which received a new lease on life when it was published in May 1934 in Der Stürmer, in the notorious issue devoted to “ritual murder.”

May 1st, 1934 issue of Der Stürmer, front page and the page with Simon of Trent.

This Nazi rediscovery of Simon in 1934 was not incidental. In 1933, the Nuremberg Chronicle, forgotten like the woodcut of Simon, was published in a gorgeous facsimile in Leipzig, no doubt drawing new attention to this woodcut. (In my study of the dissemination of the blood libel stories I found that the Nuremberg Chronicle was cited only once among hundreds of books—in the 1670 Abregé du process fait aux juifs de Mets by Abraham-Nicolas Amelot de La Houssaie.)

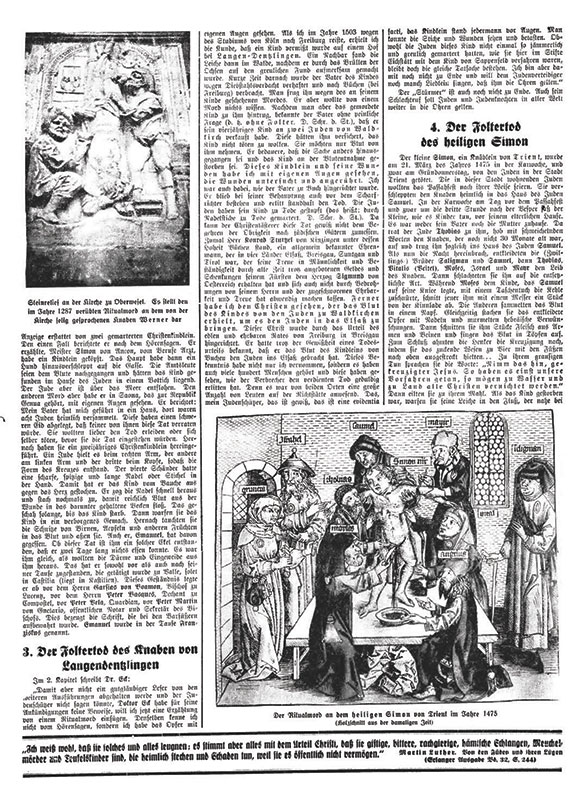

In 1943 and in 1944, the woodcut of Simon—along with several others from the 1934 issue of Der Stürmer—was included in the Nazi book by Hellmut Schramm, Der jüdische Ritualmord.ii

Hellmut Schramm Der jüdische Ritualmord (Berlin, 1944).

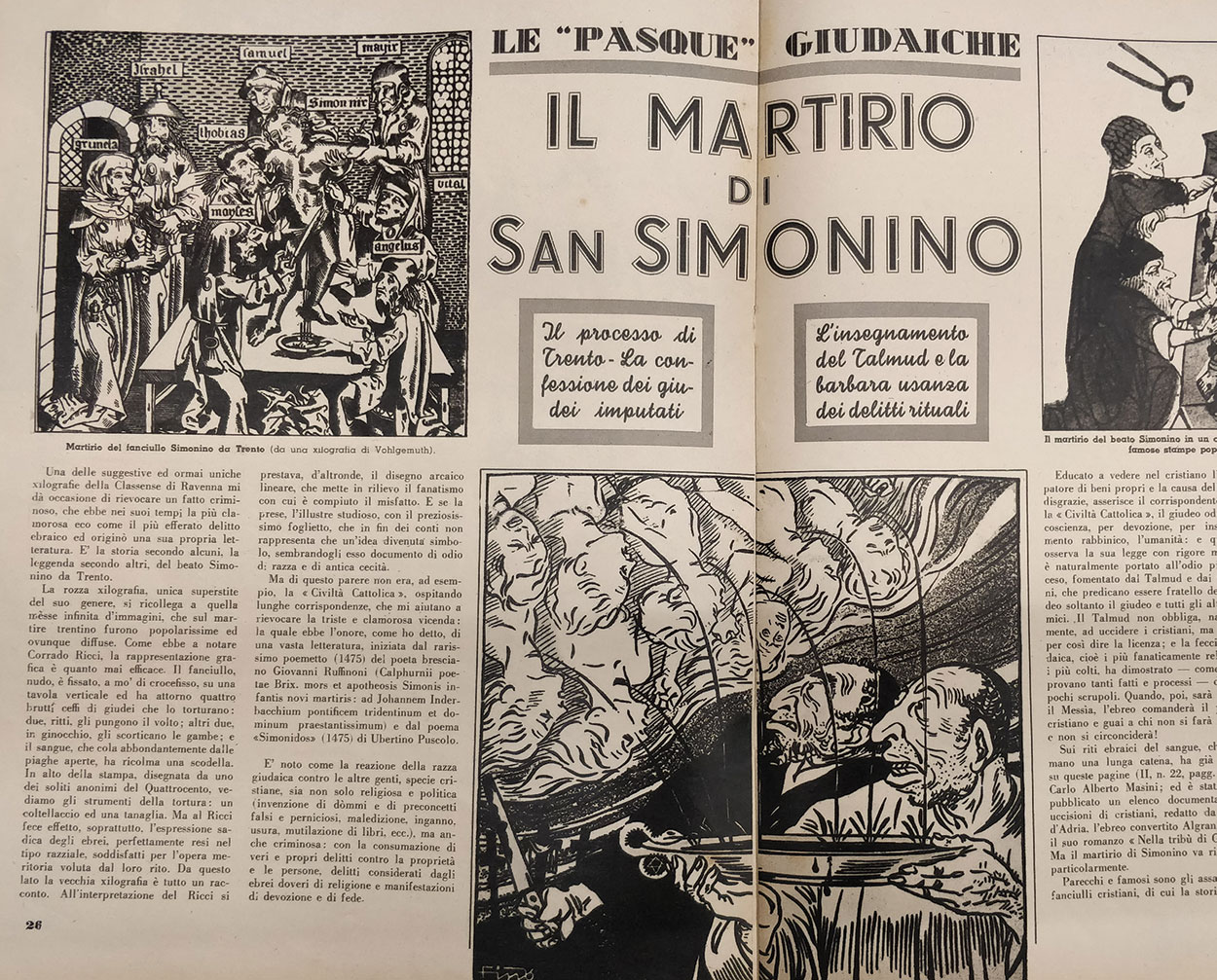

The influence of the 1934 issue of Der Stürmer was also palpable in Italian fascist publications. The March 5, 1942, issue of La difesa della razza, an Italian fascist biweekly magazine promoting racist ideas through “a scientific” approach, also devoted part of its issue to ritual murder and blood accusations, publishing select images from Der Stürmer, among them the 1493 woodcut of Simon.

Simon of Trent in March 5, 1942, issue of La difesa della razza.

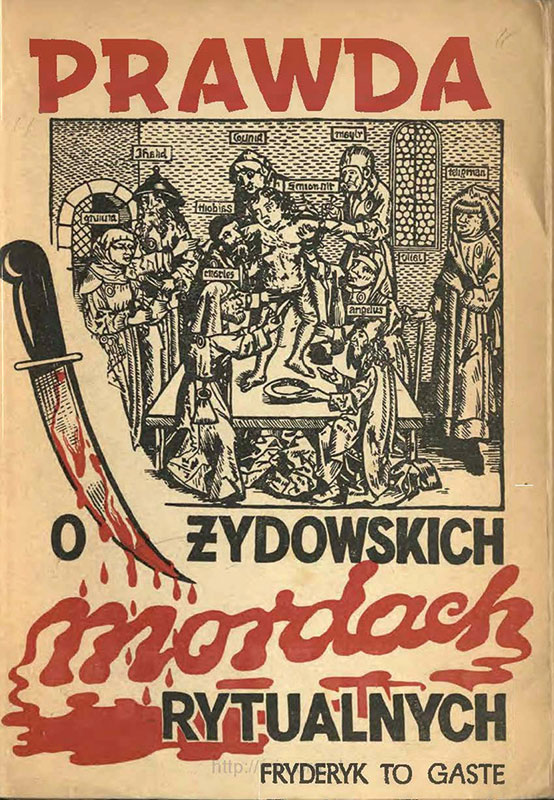

Frederyk To Gaste, Prawda o żydowskich mordach rytualnych (Warsaw: Glob, 1943).

And in 1943 the image appeared in a Polish-language Nazi publication on ritual murder, as well as in other languages, as part of the Nazi propaganda during the murderous phase of the “final solution.” Frederyk To Gaste, Prawda o żydowskich mordach rytualnych (Warsaw: Glob, 1943).

Since then the image became widely used not only by antisemites, including the neo-Nazis of our own time, but also by scholars studying antisemitism, blood libels, and ritual murder accusations. And there is little reason— aside from its intricate nature or the study of Schedel’s chronicle—to use this particular image. It was not the most influential or most reproduced. The broadsides and chapbooks published during and in the immediate aftermath of the Trent trial were far more significant in developing, as Laura dal Prà has argued, the iconographic vocabulary of ritual murder.iii Disturbingly, it seems that the reason we scholars have used it is because the Nazis popularized it as one of the most emblematic representations of ritual murder. And now, just as emblematic it was for them, so it is for us.

The troubled history of the now-(in)famous woodcut from Schedel’s Nuremberg Chronicle raises broader questions about our own sources. We modern scholars have sometimes used primary sources without examining how and why these texts and images entered circulation, or what conversations they were a part of. Jacqueline Jung, a medieval art historian, has begun to examine the role that Nazi aesthetics and ideology have played in the visual documentation of Gothic sculpture, now ubiquitously used by scholars of Medieval Studies. Lisa Leff has gestured toward this question in another context—studying Zosa Szajkowski—noting that the documents Szajkowski obtained by removing them from their original archival context shaped the historiography of French Jewry. iv

These are not trivial questions. By using sources that had been coopted by (neo-)Nazis we might be unwittingly amplifying their voices, and in today’s world this can have deadly consequences. The impact that Simon of Trent’s story and the iconic image have had cannot be more explicit than in the vitriolically antisemitic and racist manifesto written by the shooter of the Poway synagogue near San Diego, “you are not forgotten Simon of Trent, the horror that you and countless children have endured at the hands of the Jews will never be forgiven.”

Photo by © Chuck Fishman

MAGDA TETER is professor of History and the Shvidler Chair of Judaic Studies at Fordham University. Teter is the author of Jews and Heretics in Catholic Poland (Cambridge University Press, 2005), Sinners on Trial (Harvard University Press, 2011), Blood Libel: On the Trail of An Antisemitic Myth (Harvard University Press, 2020) and two edited volumes, as well as numerous articles in English, Italian, Polish, and Hebrew. In 2012-2016, she served as the co-editor of the AJS Review and in 2015-2017 as the Vice President for Publications of the Association for Jewish Studies.

i Sara Lipton, “A Terribly Durable Myth,” New York Review of Books, June 27, 2019.

ii Magda Teter, Blood Libel: On the Trail of an Antisemitic Myth (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2020).

iii aura dal Prà, "L'immagine di Simonino nell'arte Trentina dal XV al XVIII secolo" in Il Principe Vescovo Johannes Hinderbach (1465-1486), ed. Iginio Rogger and Marco Bellabarba (Bologna: Edizioni Dehoniane, 1992). Also, David S. Areford, The Viewer and the Printed Image in Late Medieval Europe (Farnham, England: Ashgate, 2010).

iv Lisa Moses Leff, The Archive Thief: The Man Who Salvaged French Jewish History in the Wake of the Holocaust (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2018).