Above: Detail from Archie Rand. 326: To Send the Impure from the Temple (Numbers 5:2), 2001-2006. From the series The 613. Acrylic on canvas. 20 x 16 in. Photo by Samantha Baskind

Scholars Insights on Art

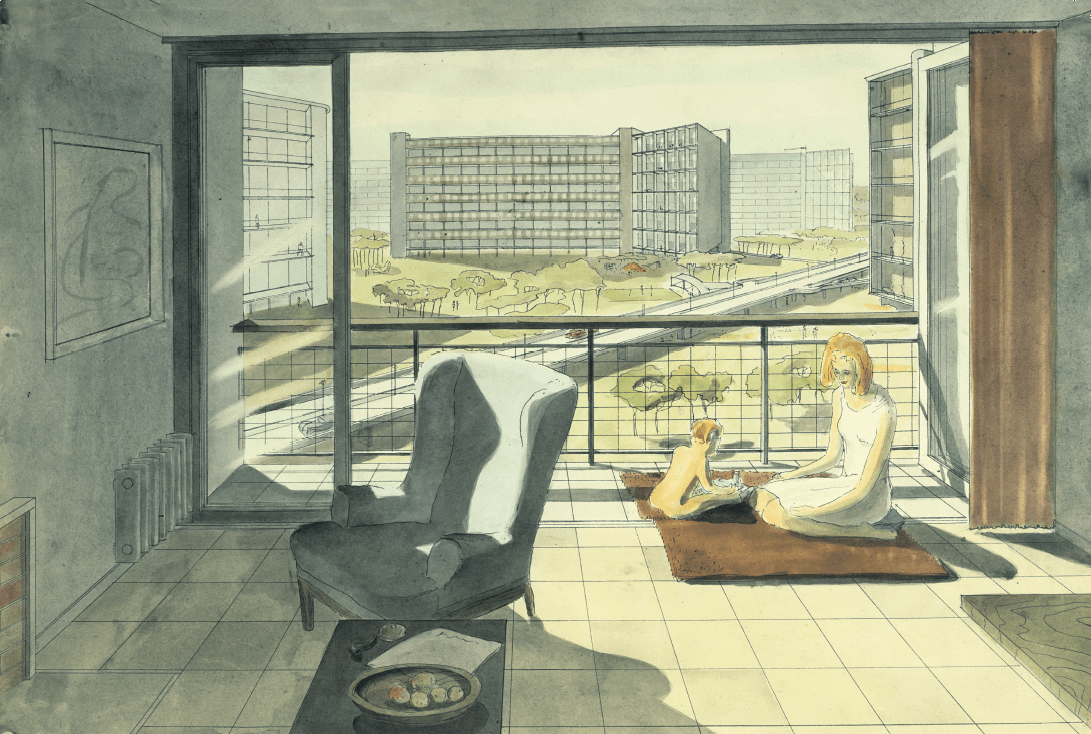

Ernö Goldfinger. Drawing of architectural enclosure, 1942. Credit: RIBA Collections. Used with permission from RIBApix.

From 1941–42, the Hungarian Jewish architect Ernö Goldfinger published a series of essays in The Architectural Review that set him apart from his contemporaries. That he had been rethinking architecture and urbanism is unsurprising. Trained in Paris and a member of various international avant-garde collaboratives, Goldfinger was well connected in the art world as a British correspondent for L’architecture d’aujourd’hui, painter, collector, and designer of furniture, exhibitions, toys, and interiors. Goldfinger was also a significant presence in the large community of migr and exiled Jewish intellectuals that settled in London in the thirties. England offered a safe haven, but there was still a lurking antisemitism. In 1935, The Architects’ Journal published a letter from an irate reader, warning against “Jewish-Communist doctrine” and referring to a Jewish tendency to “antagonize” others. The Royal Institute of British Architects required refugee architects to partner with those already registered to work, and a fear of being associated with foreigners was common. Goldfinger’s colleague Berthold Lubetkin hid his Jewish identity—for which Goldfinger labeled him a “scoundrel”— and, as many scholars have documented, Jews in midcentury England were told to keep quiet and not attract attention. Jewish-England was not English-England. Goldfinger was acutely aware of this cultural climate; his biographer Nigel Warburton reveals that Goldfinger and his wife had considered changing their surname.

Yet Goldfinger didn’t remain quiet. The 1940s essays, “The Sensation of Space,” “Urbanism and Social Order,” and “Elements of Enclosed Space,” reveal Goldfinger’s strong departures from the prevailing architectural ideals of the day through his theory of “spatial emotion”: a user’s subconscious response to architecture. Goldfinger defines architectural enclosure broadly, including buildings, streets, urban spaces, and even human interaction. He emphasizes the importance of technology, elevates the role of the artist, and highlights individual experience. The only intractable characteristic is that one cannot look at enclosed space through a photograph, drawing, or model; spatial sensation incorporates vision, sound, smell, touch, and memory. Goldfinger calls this combination the “being within.”

Goldfinger thus objectifies the conscious process of artmaking, the completed work inseparable from the artist’s psychology.

“Being within” counters both continental rationalism and the New Empiricism’s pared-down forms, the two main poles that had fallen into place by this time. While an attention to technology and art was not unusual—the machine aesthetic had led much of modernism’s search for new inspiration, and Le Corbusier, for example, had also discerned art in architecture—Goldfinger elicits from these related concerns a focus on the moment in which a work is experienced. Spatial emotion “is geographically and historically fixed,” rejecting the time-and-place-lessness of the international style’s universalism. Goldfinger’s theories reject the functionalist language of rationalist modernists, and while his conceptions of architecture and city planning are profoundly twentieth-century in spirit, even skyscrapers become creations to fulfill basic emotional needs.

For others, technocentrism had run its course, at odds with a war-torn world searching for humanity. The policy- making editors of The Architectural Review, including the important German émigré art historian Nikolaus Pevsner, suggested a return to traditional forms, linked to picturesque principles, in contrast to the abstractions of the international style they had earlier championed. For Pevsner, picturesque theories aided what would become his lifelong quest to define the Englishness of English art.

Townscape planners spoke in painterly terms of two-dimensionality (color, building outlines, roof triangles, etc.) and also discussed individual users—that is, pedestrians encountering visual surprises. Yet Goldfinger distances himself from these philosophies; planning in terms of the picture plane neglected the volumetric aspects of “being within.” He discusses high-rise structures as if an occupant were inside looking out, not a passerby looking up, his drawings often emphasizing a view through a window to the world outside.

Goldfinger takes art, technology, and the user and unites them newly, his “being within” implying another possibility. He writes, “If persons creating a work of art experience an artistic emotion while doing so … those undergoing its effects [are] enabled to experience an emotion of a similar nature.” Goldfinger thus objectifies the conscious process of artmaking, the completed work inseparable from the artist’s psychology. Goldfinger then grants the viewer the vital task of contemplating art. The existentialist-sounding language is intentional, as much scholarship has addressed the importance of existentialism in postwar British culture. In planning, an existentialist attitude helped the fifties generation undo orthodox modernism and in the arts, the tactility of art brut and abstract expressionism’s gestures came to be viewed as clear evidence of artists’ choices and the materiality of art. Yet Goldfinger is writing in 1941–42, before Jackson Pollock placed his canvases on the floor and before Jean-Paul Sartre accepted the term “existentialism.” Goldfinger has brought focused attention to the role of human expression in architecture, surely motivated by witnessing a world at war and sensing that prewar ideals and universal experiences had become irrelevant. His attitude towards the individual user separates him from the collectivity behind modernism, the welfare state’s inclusivity, and nationalistic looks to the past.

And yet, in spite of the focus on “being within,” the sense of “being without” poignantly defined Goldfinger when he wrote the essays. His biographer notes that “as a Jew with communist connections,” Goldfinger occupied a tenuous place in London society; his application for citizenship was delayed. The Goldfingers even had non-Jewish-sounding names ready for their children. This consummate insider to the art world was unwittingly an outsider. Perhaps Goldfinger’s writings on human activity and emotional responses to architecture were attempts to feel rooted in an upended world of war, living in a society in which being Jewish or foreign made things complicated.

Instead of remaining unnoticed, Goldfinger quite vocally helped shape modern London. In 1945 he was commissioned to write a book promoting the government’s proposal for postwar reconstruction. His theories inflect the book, making a somewhat paternalistic project appear forward-looking, urging residents to “think hard … [s]tudy the Plan intelligently, using their heads as well as their hearts.” The future city, it seems, requires “being within.” By the fifties, the international architectural vanguard had adopted much of Goldfinger’s language, but his insider status was always tempered by knowing his Jewish identity kept him separate from English culture.

DEBORAH LEWITTES is associate professor of Art History at the City University of New York, Bronx Community College. Her book Shaping the City to Come: Rethinking Modern Architecture and Town Planning in England, c. 1934-51 is forthcoming from Liverpool University Press in 2022. She is the author of Berthold Lubetkin’s Highpoint II and the Jewish Contribution to Modern English Architecture (Routledge, 2018).