Above: Ken Goldman. Jacob’s Ladder Triptych, 2015. Chromaluxe print after performance. Photos by Gideon Cohen

Collections of handwritten recipe books, written in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, offer us a rare glimpse into the world of early modern magical travel. Traveling tirelessly, often without either a well-paying position or social prestige, baʿalei shem (lit., masters of the name), were wonder-working healers who were tasked not only with healing individuals but also with improving communal welfare at times of calamities, such as plagues and fires. Frequently applying their skills in geographically remote areas that lacked proper access to pharmacies and university-trained doctors, baʿalei shem led an itinerant lifestyle, moving frequently from one remote community to the next. Their travel chests consisted of not much more than their prized recipe books, which functioned as a mobile apothecary dispensing both natural cures, materia medica, and supernatural remedies, materia magica, at the same time.

The travels of baʿalei shem can be conceptualized as an act of connecting not only horizontally, linking geographically distant communities, but also vertically, between different parts of the macro- and microcosm. As material objects, amulets established important correspondences between heaven and earth, Jews and non-Jews, artisanal practices and the natural world.

The wide spectrum of materials used in magical formulas draw on both particularistic and universal elements. Inside the magical travel chest, the classic textual corpora and liturgical traditions of Judaism—the Hebrew Bible, Jewish prayer, rabbinic midrash, as well as the mystical- magical teachings of Kabbalah, the hekhalot and merkavah literature—are comfortably embedded in lists of simple and common ingredients found in the domain of the household, in nature, and on the road. In a world without instant modes of communication, to be successful baʿalei shem entailed not only creatively combining and recombining what they carried in their travel chests, but also reaching their destination quickly without unnecessary delay.

Five distinct kinds of magical amulets found in these handbooks were directed to safeguard travel, because it was so central to the livelihood of this unique group of healers. The examples I comment on below were expected to provide: general protection on the road; safe passage over sea; path jumping; protection against robbers; and invisibility.

1.

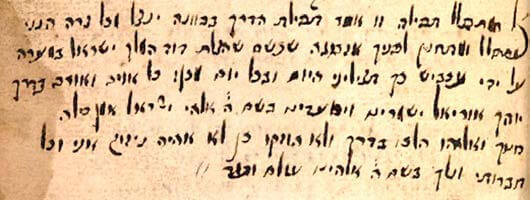

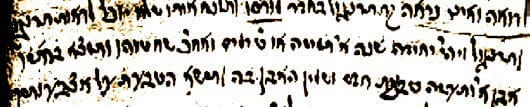

MS. British Library Oriental 10568, fol. 25r. © British Library Board

Each person who recites this prayer for the road with intention [kavvanah] will be saved from all adversity: “Behold I pray before you and entreat you, in the [divine] name that saved David, the King of Israel, in the cave with the help of a spider. Thus, may you save me today, and every day, from the hand of the enemy. Uriel, guard me and aid me in the name of the Lord, the God of Israel, amen sela. Enoch and Elijah went on the way and were not harmed. Thus, I will also not be harmed—I and my companions and we will go in the name of the Lord, our God, forever.”

Prayer intentions or kavvanot attained renewed religious significance and popularity following the circulation of esoteric teachings ascribed to Rabbi Isaac Luria (1534–1572), the preeminent sixteenth-century mystic. The centrality of kavvanot in Lurianic Kabbalah refocused attention on the interior dimensions of Jewish worship and placed human psychology and consciousness at its heart. The alignment of diverse parts of the self—the body as well as mental concentration—promoted greater efficacy for one’s prayer. Supplication and the adjuration of the angel, Uriel, are further activated by the practitioner’s mindfulness.i The magical operation is framed by the midrashic story of David’s miraculous escape from his pursuers—King Saul’s soldiers—and his ultimate rescue by a spider that God sent to weave a web over the cave he sought to hide in.ii The biblical figures, Enoch and Elijah, are presented as paradigmatic personalities associated with journeys between earth and heaven, and as such, intermediaries between these two realms. Their safe passage between seemingly contrary worlds while enjoying divine protection from the wrath of angels on their heavenly ascent could help ensure the same for the travels of baʿalei shem.

2.

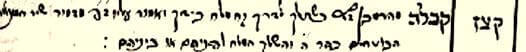

Staats- und Universitätsbibliothek Hamburg: Cod. Hebr. 135, fol. 10r. Courtesy of the Hamburg Staats- und Universitätsbibliothek

A received tradition from Naḥmanides, may his memory be blessed, [to be used] when you set out on a journey: “Take some salt in your hand, and repeat the verse seven times over it [the salt], ‘A song of Ascents, Those who trust in God are like Mount Zion that cannot be moved, enduring forever’ [Psalm 125:1]. Then cast the salt in front of them or between them [the robbers].”

This amulet is ascribed to Naḥmanides (1194–1270), the prominent medieval commentator, rabbinic leader, and kabbalist. Recipes attributed to his name recur regularly in diverse magical formulas, lending authority to their deployment and efficacy. The use of salt has been well documented in Jewish folk remedies as an effective substance against the malevolent influence of demons. The insertion of psalmic verses further activates the recipe’s efficacy and fits into the rich tradition dating back to late antiquity of using verses or entire sections of the biblical book of Psalms for diverse magical functions and frequently for producing amulets. The rules governing the use and combination of psalmic units to produce powerful angelic or divine names that could be conjured for a specific practical purpose extended to all aspects of daily life, from the protective-healing acts of childbirth, bodily aches, and exorcism, to more destructive and morbid operations of aggressive magic intended to harm, subjugate, and destroy demons or human enemies. The travel chest that managed to blend a natural substance—salt, with its primary nature to arrest expansion and growth, in this case, the malicious intention of robbers—with the apotropaic use of sacred writing—Psalm 125, with its emphasis on endurance, permanence, and protection—offered security to its owner against the countless dangers that lurked on the road.

3.

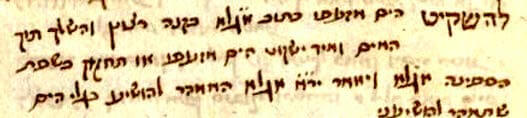

Universitätsbibliothek Johann Christian Senckenberg Frankfurt am Main, Heb. Oct. 131, fol. 72r. Courtesy of Universitätsbibliothek Johann Christian Senckenberg Frankfurt am Main

To quiet a raging sea, write the name, “אגלא,” in a continuous line and throw it into the sea and the waters will be calmed at once. Alternatively, you can etch the name, “אגלא” into the side of the ship saying, ירא אגלא, who races to save in the waves of the sea, should hasten to save me.

The recipe for a journey by sea highlights the diverse modes of travel at the disposal of baʿalei shem. The divine name אגלא is an acronym formed by the initial letters of the second of the Eighteen Benedictions (Shemoneh ʿEsreh), or Amidah prayer, the high point of the daily liturgical cycle: ʾAta gibor le-ʿolam Adonai, “You are forever mighty, Lord.” This name is frequently deployed in magical recipes especially for controlling natural elements such as fire, and in this case, to calm the waters of the sea. The apotropaic effect of the amulet is realized through the dissolution of the divine name into the surrounding waters.

4.

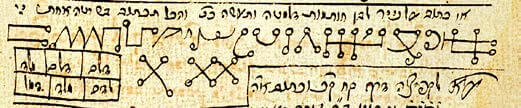

William Gross Collection, EE 011.039, Fol. 127v. Courtesy of William Gross

Write the seals below, as indicated, on white paper, and write it in a single line.

Angels seem to have their own language and alphabet, which frequently appear in magical compilations or on amulets as strangely configured magical signs called charaktêres. In this example, the angels are summoned to facilitate “path jumping” (kefiẓat ha-derekh), which allowed baʿalei shem to cover vast distances in a short time. Each of these secret alphabets is associated with a particular angel, such as Michael, Gabriel, Uriel, Metatron, and others.iii A number of how-to books I have examined contain extensive lists of alphabets, their angelic correspondence, and the Hebrew equivalent of the angelic signs so the practitioner could translate a specific command into angel language and conjure the right supernatural entity for the designated task. This amulet has another noteworthy visual element. In the left lower corner we find a 3 x 2 magical square with the permutation of the Hebrew letters, דלמ, which presumably corresponds to the angelic entity the charaktêres are meant to adjure and command.

Invisibility—a highly prized state when traveling on the road—is attained through a magical operation …

5.

The National Library of Israel, MS Heb. 8 2986, 10r. Courtesy of the National Library of Israel)

To see without being seen:

Take a chicken to the threshing room and lay it down so it could not see [anything]. It should remain [there] in isolation for a full year, or for nine days, after which he should slaughter it and take a stone from its head. He should then prepare a new ring and conceal the stone inside it and then place the ring on his finger.

The final recipe dispenses with the authority of the Jewish sacred textual canon and instead builds on universal elements of sympathetic magic. Invisibility—a highly prized state when traveling on the road—is attained through a magical operation that creates parallel dimensions of sequestered existence: the stone within the chicken and the chicken within the room, on the one hand, and the stone in the ring, and the wearer within its environment, on the other hand. Ancient Jewish magical texts, such as Sefer ha-razim, evince the use of magic rings for protection on the road, bearing the engraving of a lion and a man. Similarly, the same Sefer ha-razim prescribes the use of a dog’s head to cause sleeplessness and mental disturbance in the victim.iv Animal heads, therefore, seem to be potent mediums for inducing sensory states in human subjects, in the above recipe producing the desired effect of compromised visual abilities guaranteeing the adjurer complete invisibility.

Andrea Gondos is a postdoctoral associate in the Emmy Noether Research Group, “Patterns of Knowledge Circulation: The Transmission and Reception of Jewish Esoteric Knowledge in Early Modern East-Central Europe,” funded by the DFG (German Research Council), at the Institute of Jewish Studies, Free University in Berlin. She is the author of Kabbalah in Print: The Study and Popularization of Jewish Mysticism in Early Modernity (SUNY Press, 2020).

i Agata Paluch, “Intentionality and Kabbalistic Practices in Early Modern East-Central Europe,” Aries 19 (2019): 83–111

ii Louis Ginzberg, Legends of the Jews (Philadelphia: Jewish Publication Society, 1909), 4:4:23.

iii Gideon Bohak, “The Charaktêres in Ancient and Medieval Jewish Magic,” Acta Classica Universitatis Scientiarum Debreceniensis 47 (2011): 25–44.

iv For both examples see Gideon Bohak, “The Use of Engraved Gems and Rings in Ancient Jewish Magic,” in Magical Gems in Their Contexts, ed. Kata Endreffy, Árpád M. Nagy, and Jeffrey Spier (Budapest: L’Erma di Bretschneider, 2019), 41–43.