Above: Detail from Golan Moskowitz. A Jewish History of Drag?, 2025.

FROM THE ART EDITOR

Douglas Rosenberg

.jpg?sfvrsn=ac01d1ff_0)

Andy Warhol. Ten Portraits of Jews of the Twentieth Century, 1980. Portfolio of ten screenprints on Lenox Museum board. 40 x 32 inches each. Courtesy Ronald Feldman Gallery, New York © 2025 The Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts, Inc. / Licensed by Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York / Ronald Feldman Gallery, New York

In 1980, the artist Andy Warhol created a series of silk-screened canvases, called Ten Portraits of Jews of the Twentieth Century.

It is hard to imagine that, in the current era, an artist of Warhol’s stature would make any group, ethnic, religious or cultural, not of his own community, the subject of a similar sort of objectification.

However, Warhol, the pop artist whose body of work, more or less, reduced all of popular culture to spectacle, and who had no particular relationship to Jewishness per se (other than, perhaps most pertinently, his relationship with the art dealer Ronald Feldman, who assisted Warhol in choosing the Jewish subjects), encased his Jews within the same hyperreal, bombastic color palette and style with which he wrapped most all of his work during that era. Warhol nicknamed the series “Jewish Geniuses,” and in doing so, made his Jews first and foremost, “Warhols,” thus ameliorating any trace of the lived experience of Sarah Bernhardt, Louis Brandeis, Martin Buber, Albert Einstein, Sigmund Freud, the Marx Brothers, Golda Meir, George Gershwin, Franz Kafka, and Gertrude Stein. I have often wondered whether the number ten was a chosen number or an accidental one, an ersatz minyan, or an inconsequential accident that gives the viewer something that points to a deeper understanding of Jewish life on Warhol’s part. In the current era, we teach our students to be mindful of such trespass; to be aware of whose stories we may be appropriating and how that may fog the lens of the telling of such stories, the narratives of the individuals whose lived, embodied experience we may be, in a very real way, claiming for ourselves.

Whatever the truth of his equation, it is a bit ironic that at the end of Warhol’s career he made a return to his own Christian upbringing in the form of his Sixty Last Suppers (1986). Created near the end of his life, the series takes up the explicit themes of religion that were so seemingly absent from his previous work. He rarely spoke explicitly about his Catholic upbringing, nor did he explicitly reveal much about his own queer identity. So, in a way, Warhol remained a kind of cypher throughout his career, a kind of cultural tourist, freely able to appropriate the images of popular culture even before such appropriation came under scrutiny.

In 2020, Andy Warhol: Revelation opened at the Andy Warhol Museum in Pittsburgh, organized by the museum’s chief curator, José Carlos Diaz. In acknowledging Warhol’s complicated relationship with his faith and sexuality, curator and writer Andrew Julo noted, “In many ways, Warhol’s work also reflects a negotiated relationship between the traditional Catholicism of his childhood and his queer identity. Rather than remaining mutually exclusive, the two informed one another in an ongoing dialectic. Despite church leaders’ condemnation of homosexuality, Warhol remained devout.”

Artists working in the twenty-first century think deeply about belonging, about community, and about the politics of speaking for others, which often leads to a kind of muting of the very subjects that the artist may be aiming to elevate. In other words, what begins as a gesture of allyhood may in the end silence or tamp down the very agency of the individuals that the artist endeavors to lift up.

.jpg?sfvrsn=41dc1714_0)

Riva Lehrer. Deborah Brod, 2009, charcoal on paper with 3-D collage, 30 in. x 44 in. x .5 in. Courtesy of the artist

Not so with the work of Riva Lehrer. I can’t help but think of Lehrer’s deeply affecting series of portraits of those in her own Jewish community as a reparative to Warhol’s scattershot roundup of his “Jewish Geniuses.” Lehrer is a Chicago-based artist who is also the author of a memoir called Golem Girl, which tracks her experience as a disabled, queer Jew. In a 2024 review of Golem Girl, Sarita Sidhu describes Lehrer’s memoir: “Golem Girl is a sweeping, stunning work of visual and literary art. It is the groundbreaking memoir of an artist who has refused to be erased by a society with a rigid, very short set of rules on who deserves to live and who can and cannot be human.” The golem is often framed as a liberatory and iconic image for Jewish folks who do not fall into binary gender roles or who navigate disability. In Golem Girl, Lehrer writes, “The day I was born I was a mass, a body with irregular border. The shape of my body was pared away according to normal outlines, but this normalcy didn’t last very long. My body insisted on aberrance. I was denied the autonomy that is the birthright or normality.” With a definitive clarity of tone, the author declares, “I am a Golem. My body was built by human hands. And yet—If I once was monere [monster], I’m turning myself into monstrare: one who unveils.”

Riva Leher. Douglas and Nathan Lehrer, 2002. Graphite on Schoellershammer board, 30 in. x 40 in. Courtesy of the artist

Lehrer was born with spina bifida and “was surrounded by children with a wide range of disabilities” as a student at the Condon School for Handicapped Children in Cincinnati, Ohio, from 1963 to 1972. She writes of her time at Condon, “I had memorized the times of the day when the art room was empty and I could work in peace. The art room had always been my room.… Art was magical, and not just in the making: people would look at my work, then look at me with a changed expression. One far from the usual oh poor you.”

Over the years since, her career as an artist has become deeply involved with the field of disability culture and significantly framed by Jewish culture as well. The portraits featured here are all focused on Lehrer’s Jewish community in which there are numerous overlaps with her circle of disabled friends and colleagues. For her, making such pictures, in collaboration with her subjects, is a political gesture. As opposed to the traditional way that portraits are often fashioned, in which the sitter sits and the painter paints, Lehrer asks her subjects to work with her to create an image that speaks to the truest nature of those whom she paints.

.jpg?sfvrsn=6a9bebb9_0)

Riva Lehrer and Lauren Berlant. The Risk Pictures: Lauren Berlant, 2018. Charcoal and mixed media on paper, 44 in. x 30 in. Collection of The National Portrait Gallery of the Smithsonian Museum Courtesy of the artist

In a recent interview, Lehrer notes,

I’m not a portrait painter in the traditional sense. What I am is an artist who is trying to understand embodiment through the use of the portrait. So, I do portraits in order to understand what it means to live in a body that is socially challenged, that is critiqued, and there’s significant pressure always to be other than you are. And that includes people who are queer and trans and, to some extent, people of color, because they end up, sometimes, in situations in which they’re considered to be wrong, unacceptable.

I have no interest in just painting pictures of people for their own sake. That’s not what I do. I am analyzing what it means to have a body and the implications of having the kind of bodies that I’m portraying. And in that way, my work is political. It’s generally not seen as political because most political figuration is built around anger and resistance. And that’s not.… I could do that, but I’m more interested in the internal self. That’s what the portraits are.

As Warhol had “his” Jews, this curation of Lehrer’s work is in a way, an artistic act of responsa to Warhol’s Ten Portraits of Jews of the Twentieth Century. Warhol’s minyan was make-believe, a grouping of Jews that was fallacious, a kind of fiction compiled without any real sense of investment on the part of the artist. The group lacked any sort of animating understanding of Jews as people, as a people. Lehrer’s portraits are built with compassion and empathy for each subject, they form a community with which Lehrer has a deep understanding and kinship. It is mishpocha in the truest sense. Placing her own body at the center of her work as an artist/activist and human, Lehrer says, “I’m capital D disabled and capital J Jewish. I’m certainly capital Q queer and an artist through and through. But my body drives the train.… When I present my portrait work with people with impairments and who deal with stigma I can’t just talk about the art or some other aspect of the art … for instance, I’ll start talking about working with some trans or queer subjects and most of the time people just want to bring it back to disability. It often feels like a lot of me is left outside the door.”

As the writer Laura Martin has stated, “Riva stands squarely at the intersection of so many identities: advocate, disabled, queer, artist, writer, professor, public speaker, Jewish, and a woman.”

.jpg?sfvrsn=1ed6fe44_0)

Riva Lehrer and Lennard Davis. The Risk Pictures: Lennard Davis, 2016. Mixed media and collage on paper, 30 in. x 44 in. Courtesy of the artist

.jpg?sfvrsn=74401a99_0)

Riva Lehrer. Neil Marcus, 2007. Charcoal on paper, 44 in. x 30 in. Courtesy of the artist

.jpg?sfvrsn=c5b950f9_0)

Riva Lehrer. Nomy Lamm, 2007. Charcoal on paper, 44 in. x 30 in. Courtesy of the artist

.jpg?sfvrsn=162d108e_0)

Riva Lehrer. Rachel Youens, 2008. Charcoal on paper, 44 in. x 30 in. Courtesy of the artist

.jpg?sfvrsn=c6e83b89_0)

Riva Lehrer. Susan Nussbaum, 1998. Acrylic on panel, 16 in. x 26 in. Courtesy of the artist

.jpg?sfvrsn=7dd25643_0)

Riva Lehrer. Suspension: RR (Rhoda Rosen), 2014. Charcoal, mixed media, and acupuncture needles on board 28” x 38” x .25” Courtesy of the artist

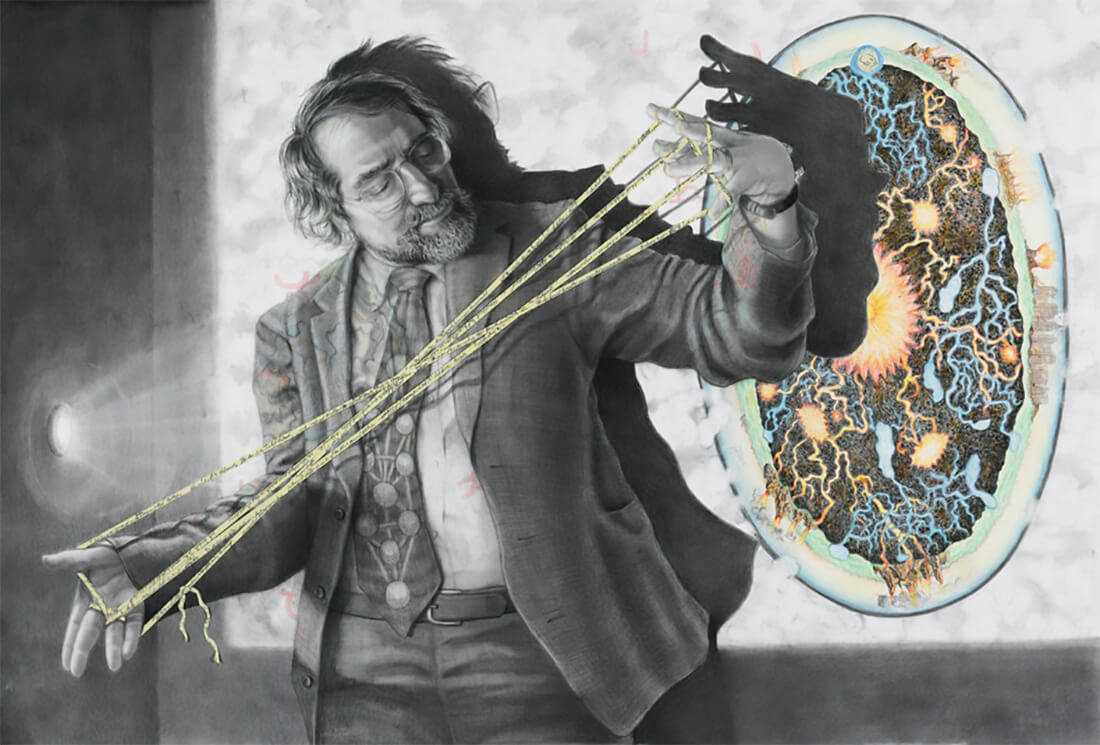

Riva Lehrer. Lawrence Weschler, 2008. Charcoal, mixed media, and collage on paper, 44 in. x 30 in. Courtesy of the artist

Links to Riva Lehrer’s work and articles about the artist:

https://www.3arts.org/artist/riva-lehrer/

https://www.zollaliebermangallery.com/riva-lehrer.html

https://www.rivalehrerart.com/gallery

https://art.newcity.com/2024/09/13/take-risks-a-review-of-riva-lehrer-at-zolla-lieberman-gallery/

https://hyperallergic.com/951840/riva-lehrer-portraits-bring-out-the-beauty-in-difference/

https://bombmagazine.org/articles/2021/12/13/riva-lehrer-interviewed/

https://disabilityvisibilityproject.com/2020/12/09/qa-with-riva-lehrer/

https://jwa.org/blog/interview-riva-lehrer-artist-and-author-golem-girl-0Loie